C. Benjamin Tracy is an author and educator, holds a Master of Science in Education, a Bachelor of Arts in English and Latin, teaching Latin. The author specializes in the Monarchy-Early Republic of Rome and the Roman-Macedonian Wars. The fascination for Alexander the Great has been lifelong, and it is expressed in the ancient autobiographical novel “In the Theater of the World”. A Macedonian translated edition is now available per request at cbenjamintracy@gmail.com. The author has received international acclaim as well as interviews in Canada and in Macedonia. Additional publications include three historical articles on Philip V and King Perseus of the Roman-Macedonian Wars, and an article on Alexander the Great’s influence on Christianity. The articles have been translated into Greek and Macedonian

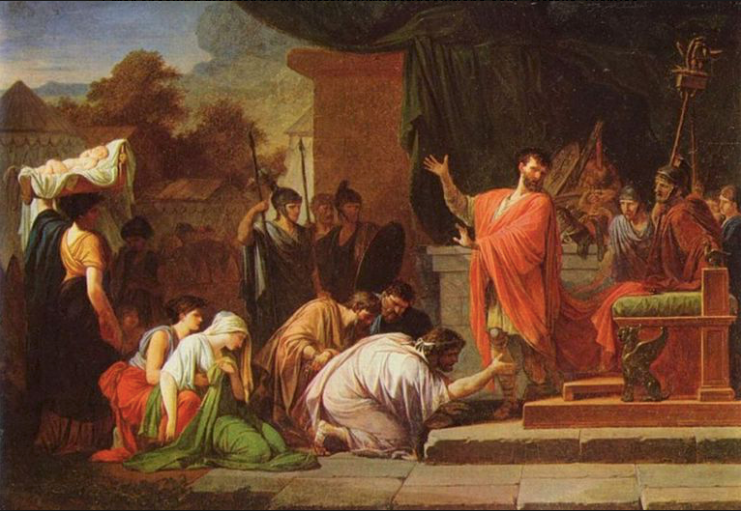

It was the end of the Third Macedonian War with Rome (171 BCE – 168 BCE). The Roman Consul, Aemilius Paullus, defeated King Perseus of Macedonia in the Battle of Pydna on June 22, 168 BCE. Historians Livy, Diodorus of Sicily and Plutarch explain in great detail the surrender of King Perseus to Paullus, and both Diodorus and Plutarch recount the procession in Rome of the victor, the defeated and his children. “Not far behind the [royal] chariot, Perseus’ children were led along as slaves… There were two boys and one girl, too young to comprehend the magnitude of the disaster – and this made people feel so much more sad for them, considering the fact that one day this incomprehension would end…many people started crying…until the children passed by…Two of [Perseus’] children died as well, but the third, Alexander, is said to have become an expert at chasing and fine engraving; also, once he had learned to write and speak the Roman language, he used to act as secretary/scribe to people in office, a job which he was found to perform in a skillful and accomplished manner.” (Plut., Aemilius Paullus. 33.7-9; 37.6).

Who was Alexander? Who was this only surviving child of King Perseus? Who was this royal Macedonian who lived in Rome? Many questions come to mind about Alexander, but only one answer had been provided, only one sentence had been contributed to the history. We do know that he had lived in a significant time during the late Roman Republic, and we know his occupation. Yet, Alexander is by that very fact significant as he does represent the continuation of the Macedonian dynastic monarchies. It is ironic that the Roman Senate knew the future of the legacy had to be eradicated and Macedonia neutralized and, yet, they still permitted Alexander to survive!

Further examination of Alexander is speculative due to insufficient resources and silent details, but is intriguing. Alexander was the last surviving descendant of the Antigonid and Argead dynasty of Macedonian kings, and he is to be explored.

What was Alexander’s age at the time of his arrival in Rome? Was he a slave of Rome? Was he a prisoner of war? Was he an immigrant who became a Roman citizen? Was he adopted during his childhood? Was their communication between him and his mother, Laodice, who also went silent in history? What were his experiences during the final war between Macedonia and Rome, the fall of Carthage, and the beginning of the fall of the Roman Republic? Did he marry and have children?

Alexander had arrived in Rome as a prisoner of war at a young age, perhaps five or ten years old. Alexander’s exact age upon his arrival in Rome is unknown, as Plutarch’s “…too young to comprehend the magnitude of the disaster” places him in early childhood. The historian Diodorus of Sicily, however, neither identifies Alexander by name nor age in his account of King Perseus’ procession in Rome: “Then came Perseus, the ill-fated king of the Macedonians, with his two sons, a daughter…” (Diod. XXXI.8.12). Livy accounts Alexander (prior to the war with Rome) standing at his father’s side on a platform while his father delivers a speech to his troops to arouse them to war against Rome (Livy XLII.52). Moreover, if we place Alexander’s birth to nine to twelve months after Perseus’ marriage to Princess Laodice of Syria in 178 BCE, the child would have been ten years old (though contradicts Plutarch’s “too young to comprehend”). This historical inconsistency offers the contemporary reader, historian and writer literary license to decide Alexander’s age.

The son of Perseus may have been sold into slavery, or assigned a guardian as a ward of the state, or been granted Roman citizenship in his adult years. Plutarch indicates slavery, yet both Diodorus and Livy do not. Conceivably, Alexander may have been assigned as a ward of the State upon Perseus’ death, as an act of Roman clemency in honor of his Macedonian royal legacy. Through custodial guardianship, Alexander may have been sponsored to learn the metalsmith trade, and later, notary training.

The mother of Alexander, Queen Laodice V, disappears in history after 168 BCE. After King Perseus and his entire family were captured in Samothrace and brought to the seacoast city of Amphipolis in Macedonia, Queen Laodice vanishes. It is assumed by historians she died between the capture of Perseus with their children, and the triumphal parade of Aemilius Paullus in Rome. Nevertheless, there is scholarship that accounts for her survival, though no evidence of her flight to Syria to seek refuge from King Demetrius I Soter. And, yet, there is no evidence of her presence in Amphipolis. It is interesting to note two facts: the symmetric occurrence of the inscribed name of “Queen Laodice” wife of Demetrius I Soter of Syria on a marble plaque dedicated to Aphrodite (post 166 BCE); and the sudden appearance of a king of Macedonia in 152 BCE by the name of Andriscus, who claimed himself to be the son of Perseus. The strong connection between Alexander, Andriscus and Laodice V is now apparent.

Sixteen years after Alexander arrived in Rome with his father and siblings (152 BCE), a Macedonian named Andriscus announced to the world he was the son of Perseus, crowned himself king, and shortly thereafter declared war against Rome. The Fourth and final Macedonian War began (149 BCE – 148 BCE). Where was Alexander during this time? What tensions may have arose in Rome with another son of Perseus residing in the city, and a potential sibling at war with Rome? The historians do not record the tension, do not draw the connection of Alexander to Andriscus, and do not even refer to Alexander. He does not exist during the Fourth Macedonian War — he, too, vanishes.

Suspicion arises as to the omission of Alexander’s presence during the final war between Rome and Macedonia, coinciding with the ascent of King Andriscus and the deaths of Demetrius I Soter and Queen Laodice V in 150 BCE. Two concurring sons of a conquered Antigonid king could have certainly threatened the security of Rome’s plan for dominion, as Carthage to the south was an ally of Macedonia through Philip V and Perseus. The Roman Senate would have been compelled to dispel any fears in the Roman people, extinguish inspiration in the slaves of Rome, and undermine support in any potential sympathizers. A persuasive rhetoric would have been broadcasted throughout Italy.

Additionally, taking into consideration Alexander was a notary of Rome, the historians’ exclusion or disregard of him thereafter is partisan and unwarranted. Alexander’s existence during this time in Rome is, indeed, deserving of attention, which may explain the lack of reference to him, other than to his occupation (Plut., Aemilius Paullus. 37.6). The Romans did not want to reinforce Alexander’s existence at the time, or, even more threatening, acknowledge the possibility of he having children. Better to ignore him.

Did Alexander have children? To insure homeland security, Rome may have attempted to prohibit him, though doubtful. Conversely, Alexander may not have wished to bring into the Roman world conquered offspring. If, however, Alexander did have children, why did not Plutarch, Diodorus and Livy report it? Again, that would have been a major occurrence to record. Was this intentional suppression or inadvertent exclusion of legacy?

Nevertheless, the final inquiry into the investigation of the son of Perseus materializes: are there descendants of the Antigonid Prince Alexander in Italy? That investigation remains open.

—

The views of the author may not necessarily reflect the views of the United Macedonian Diaspora and Generation M.