Contents

I – Introduction

II – Social Capital and the Coevolution of Formal & Informal Institutions

III – Is Social Capital Actually “Capital”?

IIII – Social Capital as Social Entitlement (Integrated with Identity)

V – A Social Entitlement and Institutional Analysis of Macedonia’s Dilemma

VI – Conclusion

VII – References

I. Introduction

Macedonia has been trapped in a perpetual identity crisis since its’ independence in 1991, with issues internally, regarding ethnic nationalism, and externally, regarding international recognition. Outcomes from this have been ‘political crisis’ and ‘weak economic policies’ which have significantly hampered Macedonia’s economic development (US AID, 2018). In 2017, Macedonia’s GDP growth rate was at 0.02%, due to low domestic consumption stemming from stagnating incomes, with more than a fifth of the country’s population remaining unemployed (US AID, 2018; World Bank, 2018a; World Bank, 2018b). Furthermore, apart from the republic’s Industrial and Technological Development Zones attracting foreign investment, overall investment levels outside of these zones are low and private sector lending is not sufficiently meeting the country’s demand (US AID, 2018). To help understand Macedonia’s predicament, this paper aims to elucidate the dynamic between identity and economic development by analysing the dilemma through an institutional lens.

II. Social Capital and the Coevolution of Formal & Informal Institutions

Douglass C. North (1990) defines institutions as ‘the rules of the game’ in a society. Such ‘rules’, North (1991) states, consist of ‘informal constraints (sanctions, taboos, customs, traditions, and codes of conduct)’ which are established by informal institutions, and ‘formal rules (constitutions, laws, property rights)’ which are established by formal institutions. Institutions exist to aid cooperation between private and public actors by defining such rules, which ‘facilitate exchange’ by producing ‘predictable human behaviour in a world of uncertainty and incomplete knowledge’ (North, 1990). Thus, the structure and stability that institutions can offer helps agents to make collective choices that would otherwise be chaotic and inefficient. Although North did well distinguishing the two forms of institutions and rules that exist, how these institutions interact with each other and how informal institutions can be defined more precisely, than the vague notion of “culture”, remain unclear (Alesina & Giuliano, 2015).

Putnam et al. (1993) make a valuable effort to expand on what informal institutions are, which they define as the ‘bundle of virtues’ which pertain to a ‘civic community’ that sum to make ‘social capital’. They state that the four virtues of a ‘civic community’ are: ‘civic participation’; ‘political equality’; ‘solidarity, trust, and tolerance’; and ‘associational life’ (Putnam et al., 1993). Putnam et al. (1993) apply this theory to the unequal economic conditions between north and south Italy, clarifying that more ‘social capital’ was accrued in northern Italy which led to better self-organisation; rules of exchange; and mutual trust in comparison to southern Italy. Thus, even after the unification of north and south Italy in the 19thcentury, and with same formal institutions being established over both regions, the north ended up better off economically as they accumulated more social capital than their counterpart from centuries before.

Woolcock and Narayan (2000) build on the social capital definition of informal institutions to develop a ‘synergy’ view of institutions, which highlights the relationship between formal institutions and social capital. Their theory states that rules, regulations, and structures founded by the state constantly interact with social organisations, which creates a feedback loop between formal and informal institutions. Woolcock and Narayan (2000) clarify that formal institutions without social commitment and involvement are ‘empty institutions’, where rules are established formally but are not respected socially. Fukuyama (1995) concurs, adding that a successful society cannot solely function on interpersonal trust (social capital), it also requires establishing formal institutions that can better enforce values and further support cooperation beyond what informal institutions can do alone.

Such theory highlights the coevolution of formal and informal institutions, and the inappropriate approach to separate the two forms when analysing institutions because of such feedback loop. Using this line of reasoning Chang (2011) points out the risks of ‘institutional imitation’, stating that simply ‘importing’ formal institutions may not produce the same outcomes seen in the exporting country, as the ‘importing country may be missing the necessary supporting informal institutions’. Both formal and informal institutions cannot be developed successfully without considering their counterpart; hence, a coevolution and co-development approach is needed for a successful institutional ecosystem to flourish.

Though there have been great strides in understanding the dynamics of institutions, it is still unclear how formal and informal institutions interact and affect each other, which in part can stem back from how informal institutions are defined as social capital (Bertin & Sirven, 2006, cited in Clary et al. 2006). Notwithstanding the definition of social capital has helped clarify what informal institutions are and has been useful in building an understanding of how institutions coevolve, the term itself is still quite imprecise ‘with multiple and often conflicting definitions’ (Robison et al., 2002). Thus, redefining social capital more accurately could help bring a better understanding to the dynamics of institutions.

III. Is Social Capital Actually “Capital”?

Arrow (1999, cited in Dasgupta & Serageldin, 1999) has been a fervent critic of the metaphor “capital” being used in defining what informal institutions are, as he states the term does not effectively capture the nuances of social networks and interactions. Capital is a specific asset that is clearly fungible and is accumulated through coherent market functions with the sole motive of being utilised to accrue more assets (Bertin & Sirven, 2006, cited in Clary et al. 2006). Concerning an agent’s motive for interacting with informal institutions, the reward is often more ‘intrinsic – that is, the interaction is the reward – or at least the motives for interaction are not economic’ (Arrow, 1999, cited in Dasgupta & Serageldin, 1999). Arrow (1999, cited in Dasgupta & Serageldin, 1999) further clarifies this with the analogy that although individuals can ‘get jobs through networks of friendship or acquaintance’, they do not often solely join social networks for this reason. Thus, informal institutions have more complex purposes than capital’s explicitly singular purpose of accumulating more assets. Additionally, informal institutions are not clearly fungible and are not exchanged effectively through market functions, as capital is (Bertin & Sirven, 2006, cited in Clary et al. 2006).

Clark and Mills (1979), who distinguish the existence of two key relationships in social networks, being exchange and communal relationships, help explain how informal institutions behave. For agents that may not be closely related to an informal institution, such as strangers and acquaintances, an exchange relationship is often established which can mimic the functions of capital (Clark & Mills, 1979). Although the exchange in this relationship is still not clearly fungible and is not exchanged through market structures as capital is, it does mimic capital exchange in the sense that ‘benefits are given with the expectation of receiving a benefit in return’; thus, ‘the receipt of a benefit incurs a debt or obligation to return a comparable benefit’ (Clark & Mills, 1979). Observations of this kind of social exchange can explain the misinterpretations of ‘social capital’ being sufficient in defining social network behaviour. However, this type of relationship is often reserved for agents who do not have a strong tie to a certain informal institution; hence, they do not reap the full capacity of benefit from said social network. Furthermore, this perspective would only explain the behaviours of informal institutions towards a subset of agents who are not very participatory.

For agents that are closely related and very participatory in certain informal institutions, such as family and friends, a communal relationship is more likely to be established (Clark & Mills, 1979). Within a communal relationship, how exchange is carried out completely deviates from how capital is exchanged, in the sense that benefits are not given contingently (Clark & Mills, 1979). In this type of relationship benefits are given in support of one’s welfare, and if an agent believes a benefit is solely given in response to past benefits received the relationship is compromised, as the assumption of mutual consideration towards their welfare is called into question (Clark & Mills, 1979). Agents that have this type of relationship within social networks are most likely to reap the full capacity of benefits, as what is of utmost focus is the agent’s welfare.

The core of most significant informal institutions derives from communal relationships, whereas at the fringe of such institutions exchange relationships are established for agents estranged or not substantially participatory. Thus, a big part of social network behaviour can be understood by communal relationships, not solely by the capital-esque exchange relationships that only explains the lesser part of informal institutions. With such nuance to social networks, if informal institutions are to be redefined more accurately the “capital” metaphor is insufficient, as it is evident that the metaphor can be misleading and myopic.

IIII. Social Capital as Social Entitlement (Integrated with Identity)

Bertin and Sirven (2006, cited in Clary et al. 2006) highlight anthropological literature which indicate that social networks follow normative obligations that depart from how capital goods are exchanged. Agents within informal institutions have access to benefits and resources based on “entitlements” (Bertin & Sirven, 2006, cited in Clary et al. 2006). Additionally, anyone who desires support requires being ready to provide support to network members in return (Bertin & Sirven, 2006, cited in Clary et al. 2006). Regarding communal relationships, this readiness to give support to “entitled” members is non-specific, whereas exchange relationships can be contingent on receipts of social exchange. Nevertheless, this rights-based approach to access resources in informal institutions differs greatly to how capital goods are accessed, where such entitlement-based exchange does not exist in the market mechanism. Hence, a rights-based definition would be most suitable to adequately define informal institutions and their behaviour.

Amartya Sen’s (1981) entitlement approach can be used as a framework to help define informal institutions, which Sen used to help understand poverty and famine. The key proponent of Sen’s (1981) theory is “means to access”, as he clarifies that even when countries have enough food famines still occur, which arise when agents do not have the entitlements (such as legal rights) to command food. Sen (1981) defines such scenario as ‘entitlement failure’, which ensues when agents do not have access to certain resources due to the limitations of their networking capability. Hence, regarding poverty and famine, it is not solely to do with the resources available but also networking ‘capabilities’ agents have (Sen, 1985). Therefore, Sen (1999) proposes that rights should be established for ‘capabilities’ that are fundamental for human existence, such as ‘political’, ‘economic’, ‘social’ and ‘security’.

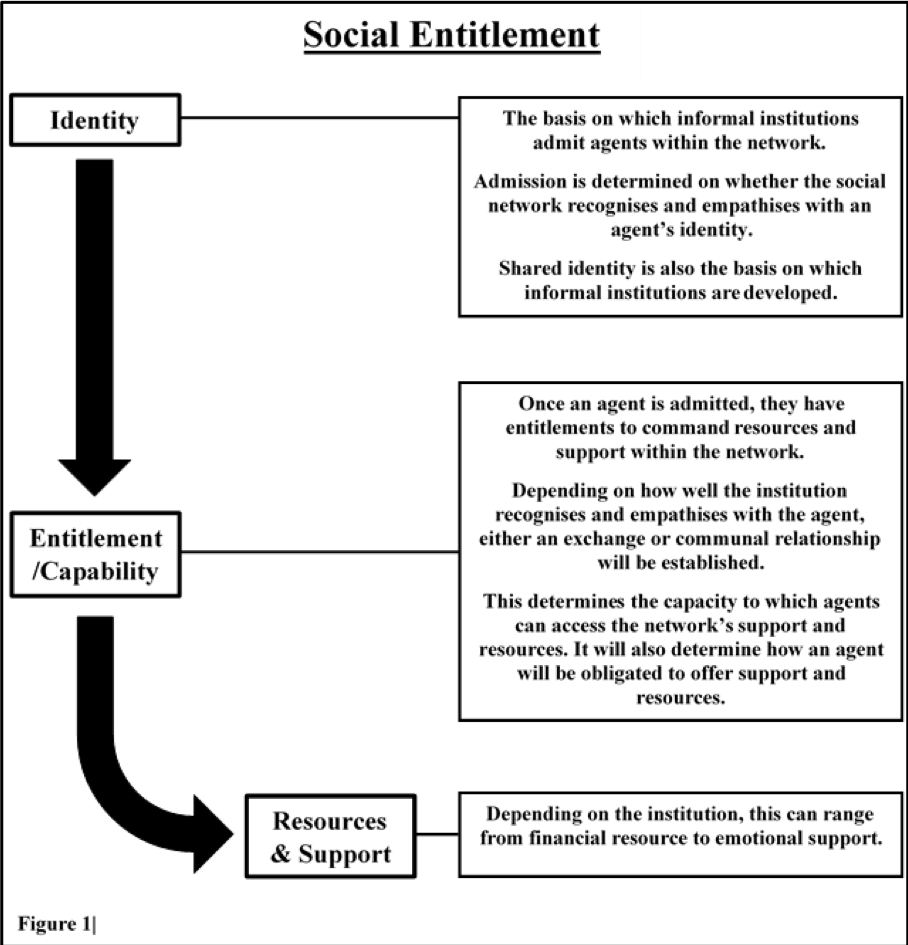

Sen’s theory nicely breaks down the functioning of social networks into the agent’s entitlements/capabilities and resources transformed from endowed or developed entitlements/capabilities. Hence, a “social entitlement” definition, deriving from Sen’s entitlement approach, would sufficiently define informal institutions and consequently brings clarity to the dynamics of formal and informal institutions. However, a limitation of using the Sen’s capability approach to define informal institutions is that ‘the framework lacks a short-list of essential capabilities’, which he refused to do ‘on the grounds of flexibility in application and social diversity’ (Davis, 2004). As a result, this limits the inferences that can be made and the effectiveness of such definition.

John B. Davis (2004) attempts to improve upon the limitations of Sen’s theory by anchoring the capability approach to ‘identity’. Davis (2011) follows the logic of Sen who implies that agents are a collection of multiple entitlements, and further builds that agents are also a collection of multiple identities (such as ethnicity, gender, class, family role etc.). The bundle of self-concepts that individuals have contain identities that are inherited (imposed) and identities that are developed by choice. An agent’s self-concepts ‘are continually being revised’ and are regularly competing for priority due to ‘conflicting demands’ (Davis, 2011). Davis (2011) states that how agents self-identify guides how their entitlements are developed, as an agent’s identity will determine the individual’s capabilities to access and build informal institutions that is required to gain resources needed. Therefore, if there are restrictions to how an agent self identifies this can lead to entitlement failure. Consequently, with identity determining agents’ interactions with informal institutions and the development of capabilities, Davis (2011) posits that identity should be protected as a human right following Sen’s logic of protecting fundamental capabilities.

With Davis’s addition of anchoring the social entitlement definition of informal institutions to identity, it gives it a base to which inferences can effectively be made and ‘preserves’ Sen’s intuition that ‘the capability framework works best when it flexibly accommodates social diversity’ (Davis, 2004). Hence, with said improvements, social entitlement more successfully defines and explains informal institutions than “social capital”. Figure 1 summarises the social entitlement definition of informal institutions.

V. A Social Entitlement and Institutional Analysis of Macedonia’s Dilemma

Recently, Macedonia’s identity and economic dilemma has come to the fore due to a referendum vote that was held September 2018. The referendum was concerning whether Macedonia should change its’ name to “North Macedonia” to resolve the 27-year name dispute with Greece. The outcome of the referendum was a resounding rejection by the Macedonian citizens, in the form of national boycotts, with ‘just over a third of Macedonians’ voting in the referendum when a ‘50%’ vote benchmark was needed (BBC, 2018). Nevertheless, against the will of the people, Macedonia’s Prime Minister Zoran Zaev secures a parliament vote to change the country’s name to ‘North Macedonia’ (BBC, 2019). Hence, Macedonian’s were essentially stuck with a choice of two unsatisfactory options, both of which would restrict the republic’s ability to self-identify. In essence, Macedonia would either be forced into an identity they do not recognise, to avoid Greece isolating Macedonia from the international community via ‘lobbying’, or maintain their current UN reference name (“F.Y.R.O.M.”) that they also do not recognise, but with hopes of leaving the door open to self-identify in the future (Sofos, 2013, cited in MIC, 2013). When citizens chose the latter option, expressing their desire to self-identify, the current Macedonian government rejected this and went against the people’s wishes.

Although the intentions of the Macedonian government are understandable, as they try to avoid global isolation incurred by Greek lobbying, they are overlooking the importance of self-identification in forming a successful institutional ecosystem. As the country has not been able to freely develop a national identity, it has not developed substantial national social networks; hence, people have turned to ethnic identifications that yield stronger informal institutions. Consequently, this has led to ethnic identities becoming ‘polarised’ and even divisively ‘mobilised’ to benefit in-groups, particularly between the ethnic Macedonian majority and ethnic Albanian minority (Adamson & Jović, 2004). Macedonia’s formal institutions further reinforce this, as within the political framework ethnicity is heavily ‘politicised’ to the extent that a majority of political parties are based on ethnic identification (Adamson & Jović, 2004). This has led to political instability and violence for the country, with World Bank (2018c) giving Macedonia a low rank of 37.14% for ‘political stability and absence of violence’ in 2017. Such conflict and political instability has been a major setback for Macedonia progressing economic development, as it is ‘regarded by economists as a serious malaise harmful to economic performance’ (Aisen & Veiga, 2011).

Although, Aisen and Veiga (2011), through quantitative testing, have found that ethnic heterogeneity is harmful to economic development. They present that lower ethnic homogeneity connote less social cohesion, which results in weak institutions and economic policies (Aisen & Veiga, 2011). Thus, it could be argued that the crux of Macedonia’s dilemma solely boils down to the republic being too ethnically diverse and that self-identification is irrelevant.

However, there are outlier cases that can elucidate more nuance regarding what Aisen and Veiga found and implied from their statistical assessments. One example is the similarly ‘landlocked’ Switzerland which is very successful with its’ economic development, as the nation is one of the ‘richest’ and most developed countries in the world, although it has a high degree of ethnic heterogeneity (Wachter et al, 2018; Weder and Weder, 2009). A key difference between Macedonia and Switzerland is that Switzerland has a national identity that citizens identify with. Consequently, Swiss citizens can interact and form successful national social networks in which they can effectively develop their capabilities and support one another, rather than falling back on ethnic identification which tends to be conflicting, divisive, and negative for a nation’s prosperity. Hence, from this comparison, it seems more likely that the crux of Macedonia’s dilemma is the nation’s restricted ability to self-identify. However, to be able to consolidate such hypothesis further case study testing would be necessary.

Nevertheless, such analysis does highlight the importance of self-identification for Macedonia. As from a social entitlement and institutional examination, Macedonia’s deprivation of self-identification has led to ethnically divided social networks, and as institutions coevolve this has influenced the state to be ethnically divided. Thus, this has ultimately led to Macedonia having an unhealthy institutional ecosystem breeding political instability and conflict that has severely affected the nation’s economic development. Therefore, it would be advisable for the current Macedonian regime to take more consideration towards supporting the republic’s will to self-identify, rather than sentencing the country to an identity that the citizen’s do not relate to, otherwise the same internal turmoil will likely continue hampering the nation’s economic development and wellbeing. In sum, a multi-ethnic democratic Macedonia can be successful if the citizens additionally have a mutual identity they relate to, as the example of Switzerland would suggest.

VI. Conclusion

To conclude, this paper aids in understanding Macedonia’s dilemma by elucidating the dynamic between identity and economic development through institutional analysis. This is done by reviewing the current literature on institutional economics and revising some of the theory. The definition of “social capital” was revised to “social entitlement” through the work of various social scientists, with two key contributions coming from Amartya Sen and John B. Davis. Additionally, a model was created, in which both definition and model integrate identity in their explanations of informal institutions. This was done to improve the understanding of institutions and their dynamics. Social entitlement and institutional analysis hints that Macedonia’s restricted ability to self-identify has negatively affected their ability to develop a healthy institutional ecosystem, which consequently has negatively affected their economic development.

VII. References

Adamson, K. and Jović, D. (2004) ‘The Macedonian–Albanian political frontier: the re‐articulation of post‐Yugoslav political identities’. Nations and Nationalism. 10(3) pp. 293-311.

Aisen, A. and Veiga, F.J. (2011) How Does Political Instability Affect Economic Growth?.IMF. Available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2016/12/31/How-Does-Political-Instability-Affect-Economic-Growth-24570[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

Alesina, A. and Giuliano, P. (2015) ‘Culture and Institutions’. Journal of Economic Literature. 53(4) pp. 898-944.

Arrow, K.J. (1999) ‘Observations on Social Capital’. In Dasgupta, P. and Serageldin, I. (1999) Social Capital: A Multifaceted Perspective. Washington: The World Bank.

BBC (2018) Macedonia Referendum: Name Change Vote Fails to Reach Threshold.BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-45699749[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

BBC (2019) Macedonia Parliament Agrees to Change Country’s Name.BBC. Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-46846231[Accessed: 15 January, 2019].

Bertin, A.L. and Nicolas, S. (2006) ‘Social Capital and the Capability Approach’. In Clary, J.B., Dolfsma, W. and Figart, D.M. (eds.) (2006) Ethics and the Market: Insights from Social Economics. Marquette: Routledge.

Chang, H. (2011) ‘Institutions and economic development: theory, policy and history’. Journal of Institutional Economics. 7(4) pp. 473-498.

Clark, M.S. and Mills, J. (1979) ‘Interpersonal Attraction in Exchange and Communal Relationships’. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 37(1) pp. 12-24.

Davis B.J. (2004) ‘Identity and Commitment: Sen’s Conception of the Individual’. Tinbergen Institute. 2(55) pp. 1-31.

Davis B.J. (2011) Individuals and Identity in Economics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Fukuyama, F. (1995) Trust: The Social Virtues and the Creation of Prosperity. New York: Free Press.

North, D.C. (1990)Institutions, Institutional Change and Economic Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

North, D.C. (1991) ‘Institutions’. The Journal of Economic Perspectives.5(1) pp. 97-112.

Putnam, R.C., Leonardi, R. and Nonetti, R.Y. (1993) Making Democracy Work:Civic Traditions in Modern Italy. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Sen, A. (1981) Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1985) Commodities and Capabilities. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sen, A. (1999) Development as Freedom. New York: Oxford University Press.

Sofos, S.A. (2013) ‘Beyond the Intractability of the Greek-Macedonian Dispute’. In MIC (eds.) (2013) The Name Issue Revisited: An Anthology of Academic Articles. Skopje: MIC.

USAID (2018) MACEDONIA: ECONOMIC GROWTH. USAID.Available at: https://www.usaid.gov/macedonia/economic-growth-and-trade[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

Wachter, D., Egli, E., Maissen, T. and Diem, A. (2018) ‘Switzerland’. Encyclopaedia Britannica. [Online] Available at: https://www.britannica.com/place/Switzerland/Introduction[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

Weder, B. & Weder, R. (2009) Switzerland’s Rise to a Wealthy Nation: Competition and Contestability as Key Success Factors. Research Paper 2009/025. Helsinki: UNU-WIDER.

Woolcock, M. and Narayan, D. (2000) ‘Social capital: implications for development theory, research, and policy’. The World Bank Research Observer. 15(2) pp. 25-249.

World Bank (2018a)GDP growth (annual %). World Bank. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.MKTP.KD.ZG?locations=MK[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

World Bank (2018b)Unemployment, total (% of total labor force) (modeled ILO estimate). World Bank. Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.UEM.TOTL.ZS?locations=MK[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

World Bank (2018c)Worldwide Governance Indicators. World Bank. Available at: http://info.worldbank.org/governance/wgi/#home[Accessed: 20 December, 2018].

—

The views of the author may not necessarily reflect the views of the United Macedonian Diaspora and Generation M.

%20(2).jpg)

The coup de grace of Greek arguments. The final stake in the heart of the Macedonian identity. After all, how could we be Macedonians when 2,500 years ago, our ancestors wrote their coins in Greek? I suppose this is the new litmus test for all people’s identities. When we find the ancestors of the French once wrote in a Celtic language, President Macron will be in for a shock that he can’t truly be French. Of course, we know that Greek was the lingua franca of the Mediterranean world and there are coins in Greek all the way in Afghanistan. The u

The coup de grace of Greek arguments. The final stake in the heart of the Macedonian identity. After all, how could we be Macedonians when 2,500 years ago, our ancestors wrote their coins in Greek? I suppose this is the new litmus test for all people’s identities. When we find the ancestors of the French once wrote in a Celtic language, President Macron will be in for a shock that he can’t truly be French. Of course, we know that Greek was the lingua franca of the Mediterranean world and there are coins in Greek all the way in Afghanistan. The u