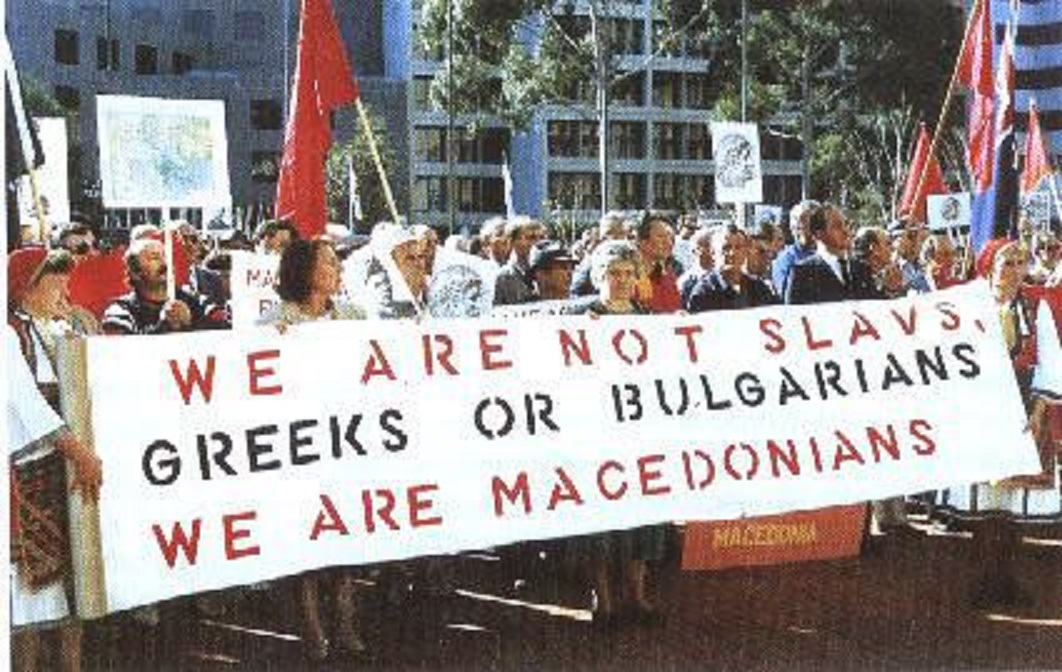

Slavo-Skopijans. Slavo-Bulgars. Slavo-Tito-Vardarskians. For a people claiming descent from the great rhetoricians such as Demosthenes and Aristotle, our Greek friends find it incredibly difficult to conjure a cogent and scathing insult against us. Any derivative with the “Slav” prefix seems to be the end-all, be-all argument. After all, it is the Slav communists, together with the Jewish bankers, and the Turkish army that conspire against the Greeks in a fantastic, global, anti-Hellenic conspiracy. For those who have not uttered the name “Macedonia” on social media only to be hounded by a nameless, faceless, group of Greek internet warriors pasting the same canned responses ad infinitum, the Greek narrative usually goes something like this:

The barbaric Slavic tribes came from the swamps of the Ukraine to the Balkans in the 7th century. Presumably, they were either turned back at passport control at the modern Medzhitlija-Niki border crossing, or they found Macedonia completely de-populated, since the modern-day Greeks completely escaped the Slavic incursion. Somehow, these wandering Slavs managed to displace the Byzantine Empire and impose their language on most of Eastern Europe, while it was the gracious Greeks to gifted them their alphabet. Fast-forward to Tito and 1944, and these subhuman Slavs, now communists, wanting to usurp the proud “Hellenic” history, were artificially made Macedonians by Tito in a bid to annex Greek land. And they’ll show you an out-of-context stamp [1] to prove it! The Jews are also probably complicit here, but one paranoid delusion after the next.

So what exactly are “Slavs”? Besides the so-called “usurpers” of Greek history, are modern-Macedonians really the result of a recent colonization to the Balkans? Let’s start with the word “Slav” itself and branch out. The world “Slav” comes in its present form from the Latin Scalvus which, in turn, comes from the Byzantine Greek Σκλαβηνος (Sklabenos), which was ultimately a corrupted form the Slavic relation term словѣне (Slovene). “Slovene” according to most linguists, comes from the Slavic-root слово (slovo) meaning “word”. Put differently, the “Slavs” were a group who could reasonably understand each other, as opposed to the German “Nemci”, whose name literally means “mute”. So did the tribe of the “Word People” somehow manage the greatest demographic displacement in history? There are detailed records of the migration of the Anglo-Saxons, Normans, Goths, Tartars, Mongols, Turks, and other groups yet the Slavic-migration, which would be arguably one of the most massive migrations in recent history, went virtually unnoticed by historians. This begs the question–could the Slav label simply be a new reference for existing populations undergoing a dramatic linguistic and political shift?

Let’s look at it piecemeal.

Historical Evidence

The first time the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire came across these Slavs was under the reign of Justinian in the 6th century, by which time a group of barbarians (non-Greek speakers [2] ) from across the Danube river began to regularly attack the Empire. Beforehand, the Balkans were home to the Illyrians, Greeks, Macedonians, Dacians, Triballians, Thracians, Veneti, Sarmatians, and Scythians to name a few. Most sources placed the Slavic-speaking tribes right along the Danube River, and no source indicates a recent arrival instead referring to them as “our Slavic neighbors”[3]. In fact, Byzantine chronicler Theophylact Simocatta gives an interesting perspective as to what Slavs (Sklaebenes) could have meant to Byzantine administration. He states, “As for the Getae, that is to say the herds of Sklabenes, they were fiercely ravaging the regions of Thrace”[4]. The Getae, however, were an indigenous Thracian tribe that has been recorded since ancient times [5]. It is clear that they did not migrate from anywhere, nor were they previously called Slavs until this moment in history. A possible explanation is that they became labeled Slavs because they, along with other tribes, began revolting against and attacking the Byzantine Empire. More importantly, it was not limited to the attackers; it soon became used to refer to local populations who also rebelled against the empire; some Slavic “tribal” names, such as the Timochani [6], Strymonoi [7], Caranatianians [8] are indigenous Balkan place names, having existed long-before the Slavs ever arrived.

Therefore, Sklabenes, based on Slovene, came to signify a rebel, with a derogatory connotation. In other words, they did not become Slavs because they exclusively spoke in a Slavic tongue. In fact, some Slavic tribal names have Iranian [9] and Nordic [10] roots. Even though some groups may have used Slavic languages as a lingua franca [11], the important takeaway is that they all became Slavs because at least some of the participating groups used the relational term Slovene to signify kinship. By the time indigenous pockets of population began to ally themselves with the Slavic-speaking groups and started forming rebel enclaves called Sklavinaes, the derogatory term became synonymous with an anti-Byzantine rebel or marauding barbarian. As Florin Curta, leading archaeologist and historian on the early Slavs says in “Making of the Slavs, “Instead of a great flood of Slavs coming out of the Pripet marshes, I envisage a form of group identity which could arguably be called ethnicity and emerged in response to Justinian’s implementation of a building project on the Danube frontier and in the Balkans. The Slavs, in other words, did not come from the north, but became Slavs only in contact with the Roman frontier” [12].

The idea that the people who became labelled the Slavs in the 6th and 7th century were, for the most part, the same people who existed previously has found more support in modern academia. “It is now generally agreed that the people who lived in the Balkans after the Slavic “invasions” were probably for the most part the same as those who had lived there earlier, although the creation of new political groups and arrival of small numbers of immigrants caused people to look at themselves as distinct from their neighbors, including the Byzantines. [13]” Italian anthropologist Mario Alinei states the Slavic-migration is full of inconsistency, demonstrating that both linguistic and archaeological evidence points to the earliest presence being the in the Balkans [14]. Even the taboo subject of speaking of modern Macedonians in books on ancient Macedonians is slowly being breached. In his book, By the Spear Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire, British historian conceded the point that the ancient Macedonians may have been a Slavic-people that “fell under heavy Greek influence and embraced their culture”[15].

Genetic Evidence

I believe that genetic testing to prove how pure someone is not only incredibly myopic, but only diminishes the best among us. After all, some of the greatest Macedonians in history have been either partially Macedonian or not at all ethnically Macedonian. Many Aromanians and Jews that fought for the independence of Macedonia are just as Macedonian as we are. But since this is the game of racial identities we are forced to play, we must nonetheless defend ourselves. Modern research has revealed the fallacy of using such an approach to explain our “Slavic” origins. In an attempt to solidify the homeland of the  Slavs, geneticists isolated a special haplogroup-, a group of similar DNA variations, to be the “Slavic gene”. Named Haplogroup R1a, it naturally showed its highest frequencies in Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus, averaging 65%-70% [16] . In the Southern Balkans, however, the national frequencies averaged only about 15%, not nearly enough to show evidence of mass-migration. More troublesome for the Slavic Migration Theory is that some Scandinavian countries show a higher frequency, about 30%, than the Southern Balkan populations. Furthermore, the one haplogroup that is the highest defining haplogroup for the region, Haplogroup I2, is simply labeled “Southern Proto-European”. This is not shocking; modern Macedonians differ even anthropologically from the so-called Slavs, described as being tall and with reddish blonde hair, a trait much more frequent in Central Europe [17].

Slavs, geneticists isolated a special haplogroup-, a group of similar DNA variations, to be the “Slavic gene”. Named Haplogroup R1a, it naturally showed its highest frequencies in Poland, Ukraine, and Belarus, averaging 65%-70% [16] . In the Southern Balkans, however, the national frequencies averaged only about 15%, not nearly enough to show evidence of mass-migration. More troublesome for the Slavic Migration Theory is that some Scandinavian countries show a higher frequency, about 30%, than the Southern Balkan populations. Furthermore, the one haplogroup that is the highest defining haplogroup for the region, Haplogroup I2, is simply labeled “Southern Proto-European”. This is not shocking; modern Macedonians differ even anthropologically from the so-called Slavs, described as being tall and with reddish blonde hair, a trait much more frequent in Central Europe [17].

However, if were to look at the same primary sources and come up with a theory of a great migration, we must take that premise to its logical conclusion. The so-called Slavs, if part of a massive migration, reached into the Southern Greek Peloponnesus region, meaning Greeks are also partially Slavic. It was by no chance that German historian and linguist Max Vasmer’s work in the 1900s, discovered more than 1,300 Slavic place names scattered all throughout Greece [18]. So our Greek friends have an “either or” conundrum at hand–either the Slavic incursions and raids weren’t part of a massive migration, or they were, and most of the Balkans would have been affected by it. But then again if Albanian speakers in the Attic region [19] can magically become descendants of ancient Hellenes by speaking Greek, “abdication from reality” seems to be the filled-in answer for some Greek nationalists.

Cultural Evidence

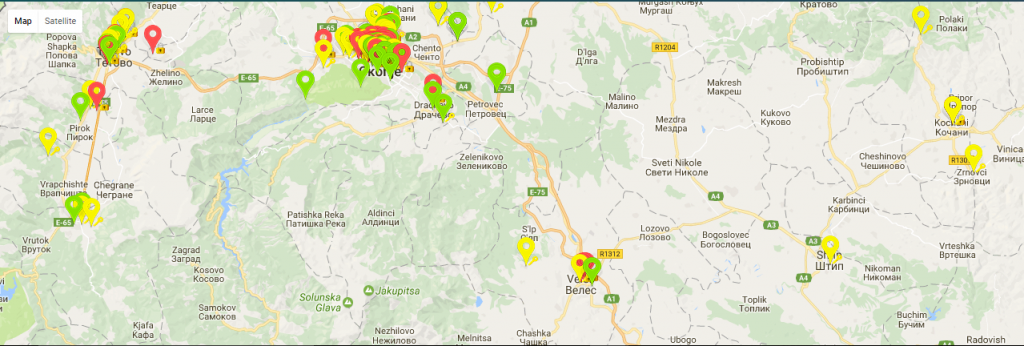

It is a modern travesty that archaeologists and historians alike go to the far-reaches of Pakistan to look for the remnants of the ancient Macedonians, while completely glossing over the treasure trove of information our culture has to offer. The very core of ancient Macedonia has remained part of our national identity for centuries. Kostur, from whence the Macedonian kings descended, is still proudly Macedonian-speaking. Beautiful Voden, rumored to be the first capital of Macedonia, has a mythical founding by King Perdicas that has found its way into the pages of the Brothers Miladinov in the mid-1800s. Pella, the seat of Macedonian power and the city where Alexander took his first steps, was the birthplace of the modern Macedonian language by way of its native, Krste Petkov Misirkov. The list goes on. Our churches were adorned with the Macedonian sun in the 1800s, more than a century before Greece “discovered it”. Our national animal since ancient times has been the lion [20], showing up in our modern coat of arms as early as 1314. Not only has Greece never decided to usurp this otherwise obvious symbol of Macedonians, but by the time the so-called Slavs came to the Balkans, the lion had been long extinct in Macedonia. Our songs and folklore, once performed by our illiterate peasants, have songs about Alexander, Phillip, Olympia, Caranus [21], and Perseus [22] to name a few. In 1867, a traveling Jewish salesman (deep breaths, Golden Dawn) was amazed when he heard the Hazhi-Sekov brothers sing of King Caranus [23], the mythical if albeit obscure first king of Macedonia. When asked how they knew such a song, they replied they learned it from their grandfather! Even our first constitution, from the Kresna Uprising in 1878, makes explicit reference to Alexander the Great in its preamble. Defying modern science, our uneducated villagers also knew that Alexander died of a mosquito bite, decades before British researcher Ronald Ross hypothesized this in 1878, and some 100 years before it was universally confirmed that mosquitoes carry malaria. For all this rich cultural heritage, there is conspicuously not one song or folklore tradition detailing our supposed migration from the great Carpathian mountains.

Linguistic Evidence

As Macedonians, we lose little by conceding we do, in fact, speak a Slavic language. Many nations today speak a completely different language than they did in ancient times. But seldom has our language, and the language of our ancestors been properly studied. After all, by virtue of being “Slavs”, we are immediately disqualified from having a seat at the table. Nonetheless, our language proves a degree of continuity between ancient and modern Macedonians.

- The Bryges, the ancestors responsible for the ethnogenesis of the Macedonian people, have a tribal name akin to the Slavic root БРЕГ meaning “hill”, an adequate description for hillsman of ancient Macedonia [24].

- Stobi the Paeonian city, now an archaeological site in modern Macedonia, has a name deriving from the modern Macedonian words СТОЛБ meaning “pillar”, possibly denoting the presence of a religious temple there.

- While Greeks may claim the true name of Voden is “Edessa”, ancient history shows the original name was ΒΕΔΥ (B/Vedu), meaning “watery”, a clear cognate that shows remarkable continuity by way of of the modern name, Воден [25].

- German linguist Heinrich Tschiner, in his lexicon of the ancient Macedonian language, has determined the city of Pella, to be a cognate with the modern-day term ПОЛЕ, meaning “field” [26].

- The Macedonian-Paeonian city of Bylazora, containing the last temple of ancient Macedonian kings, comes from the Slavic roots БѣЛъ and ЗОРА meaning “white dawn”.

- The ancient Macedonian city of Gortunia, lacking any etymology in Greek, is remarkably similar to the proto-Slavic root ГОРДъ meaning “city”.

- Modern-day basic Macedonian words such as ГЛАВА [27] (head), ГРАНКА [28](branch), ГУДЕ [29] (pig), ЗЕЛКА [30] (cabbage) also have roots in the ancient Macedonian language.

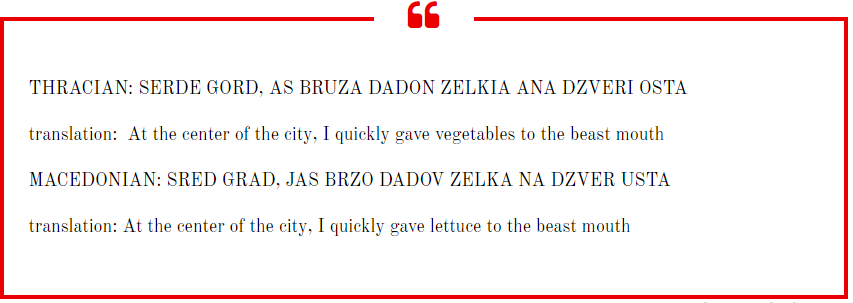

Furthermore, there are ancient Macedonian words that are not present in Macedonian, but in other languages grouped in the wider Balto-Slavic linguistic classification [31]. Slavic words that show up in antiquity do not end there, as it is also found in Illyrian, Thracian, and even Homeric Greek [32]. As an example, compare the following hypothetical sentence, constructed entirely from known Thracian words and compared to modern-day Macedonian.

As for the name Macedonia? Recall that blue flower that is at the center of our sun, the ethnic symbol of Macedonians going back millennia. The Macedonian and general Slavic root for poppy happens to be “макъ”[33]. Now, I am not claiming that the ancient Balkan peoples were Slavic speakers. I am not even attempting to claim we speak the same language as the ancient Macedonians. But it is difficult to ignore the presence of Balto-Slavic words in the Balkans before the so-called Slavic migration.

However, let us not lose the forest for the trees. We can look to any number of people today who have ancient roots. Did the Egyptians become any less Egyptian when they underwent Arabization in the 7th century? Do the Mexicans, who experienced near exterminations throughout history, and who are now mixed with the Spanish and speak almost exclusively Spanish, any less descendants of the Mayans? How about the French, a people descended from the Celtic-speaking Gauls, and who have a Germanic ethonym? As a result of their Latinization, are they any less French?

But as Macedonians, even if we concede (however inaccurate) that our name is Greek, that our roots are mixed, and that our ancestors once spoke Greek, by what objective standard, applied consistently to all nations, are we excluded from being Macedonians? By what standard should we submit to being called “Slavo-Macedonians” when the world is conspicuously absent of the “Slavo-Czechs”, or the “Latin-French.” When we realize that our identity, is no different from any number of other people, the double standard becomes something much more sinister—cultural genocide. And this cultural genocide cannot succeed, so long that a small mountainous patch of earth, one that means the world to us, remains Macedonia and its people Macedonians.

Citations/Footnotes

[1] “Vardarska Banovina” was simply an administrative region of Yugoslavia, and in no way corresponded to the borders or names of any country. The same stamp also doesn’t show any country named Serbia, Bosnia, or Slovenia, but instead has their Banovina titles.

[2]Perseus Tufts Ancient Greek Lexicon Entry for “Βαρβαρος”

[3] Curta, 108

[4] Simocatta, The History of Theophylact Simocatta. IV, 4.7

[5] Encyclopedia Britannica Entry for “Getae”

[6] From the Timok River, Timacus in Latin, which flows through the duskiness of the Škocjan caves. In Slovenian Ti(e)ma means “darkness”

[7] Strumon, a river in ancient Macedonia. From the proto-Slavic *struja meaning “flowing current”

[8] Possibly derived from the Proto-Slavic *korǫt’ьsko meaning “rocky”. France Bezlaj, Etimološki slovar slovenskega jezika(Slovenian Etymological Dictionary). Vol. 2: K-O / edited by Bogomil Gerlanc. – 1982. p. 68. Ljubljana: Mladinska knjiga, 1976-2005.

[9] Curta, 11

[10] See Guduscani, etymologically related to Gothiscandza, ultimately derived from Scandza (Scandinavia)as attested in Jordanes’ Getica.

[12] Curta, 11

[13] T. E. Gregory, A History of Byzantium, pg. 169 (Edinburgh, 1855)

[14] Mario Alinei, Origini delle lingue d’Europa, Vol. I: La teoria della continuit, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1996

[15] Ian Worthington “”By the Spear Philip II, Alexander the Great, and the Rise and Fall of the Macedonian Empire” (Oxford University Press, 2014) pg. 20

[16] http://www.eupedia.com/europe/european_y-dna_haplogroups.shtml

[17] Procorpius, De Bellis

[18] Max Vasmer “Die Slaven in Greichenland” (Berlin, 1941)

[19] Edmond About, “Greece and Greeks of the Present Day”, pg. 32

[20] http://www.historyofmacedonia.org/Macedoniansymbols/MacedonianLion.html

[21] “Mihailo Georgievski “Slavic Manuscripts in Macedonia), (Skopje, 1988), pp 161-173, citing “The Anthology of Macedonian and Bulgarian Folk and Art Songs (1909-1910), pp 68.

[22] “Narodna Volya” (Blagoevgrad, July 1994).

[23] Isaija Mazhovski “Memories”, (Sofia, 1922)

[24] Müller, Hermann. Das nordische Griechenthum und die urgeschichtliche Bedeutung des Nordwestlichen Europas, p. 228.

[25] http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus:text:1999.04.0006:entry=edessa-1&highlight=vedy

[26] http://www.heinrich-tischner.de/22-sp/1sprach/aegaeis/mak-th.htm#%CE%A0%CE%99

[27] Ancient Macedonian word ΓΑΒΑΛΑ http://www.palaeolexicon.com/Word/Show/26691/

[28] Ancient Macedonian word ΓΑΡΚΑΝ http://www.palaeolexicon.com/Word/Show/21689/

[29] Ancient Macedonian word ΓΟΤΑΝ http://www.palaeolexicon.com/Word/Show/25662/

[30] Ancient Macedonian word ΖΑΚΕΛΤΙΔΕΣ: Cited by the Macedonian lexicographer Amerias, this was the ancient Macedonian word for “turnip” or “cabbage.” According to Dr. Otto Hoffmann, it is cognate to the Brygian word “ζέλκια (zelkia)” or “ζέλκεια (zelkeia)” and the old Slavic word “злакъ (zlakă)” meaning “cabbage.” ( Hoffmann, Otto; Die Makedonen, ihre Sprache und ihr Volkstrum; p. 8)

[31] Authentic Ancient Macedonians words such as ΒΕΝΔΙΣ (goddess of hunt) and ΠΕΛΙΓΑΝΕΣ (senator) are both preserved almost identically in modern Lithuanian and Latvian.

[32] Homeric familial terms such as ΔΑΒΕΡΟΣ/DAVEROS, (brother-in-law), ΣEΚΥΡΟΣ/SEKUROS (father-in-law), MAIA/MAYA (mother, older woman) are terms still used, albeit slightly changed, in modern-Macedonian. For more information see: http://stephanus.tlg.uci.edu/cunliffe/#eid=1&context=lsj

[33] https://en.wiktionary.org/wiki/%D0%BC%D0%B0%D0%BA#Etymology